I never thought I would be bored at 500 feet off the ground.

Standing on Ahwahnee ledge on the West Face of the Leaning Tower, I pace back and forth in anticipation. Or what amounts to pacing when you have less than 3 feet of space to move around in.

We were on Day 2 of our 3 day ascent of the Leaning Tower. My partner, Mike, and I had never attempted a big wall before and we were both excited and anxious to get going. We just had one problem, there was another party on the route ahead of us.

We thought we knew what getting stuck behind a slow party could mean, but as I stood on Ahwahnee ledge, staring up at Mike while he sat next to the second in the other party at the belay, I discovered a new meaning to the word patience.

The party in front of us had held us up the day before, I had sat for 3 hours at a hanging belay in the baking sun, shifting uncomfortably from hip to hip, trying to find a place that didn’t hurt to exist in.

Today however, I had been standing on this ledge, waiting to climb for over 6 hours.

We should have asked to pass them first thing in the morning.

Both of us are new to this type of climbing and we were too shy to ask the more experienced party if we could pass them, it seemed rude and out of place for us to demand to go ahead when they had 3 or 4 big wall climbs under their belts and we had 0. We sipped our cowboy coffee and tasteless oatmeal instead while we watched them rack up and prepare the haul bag.

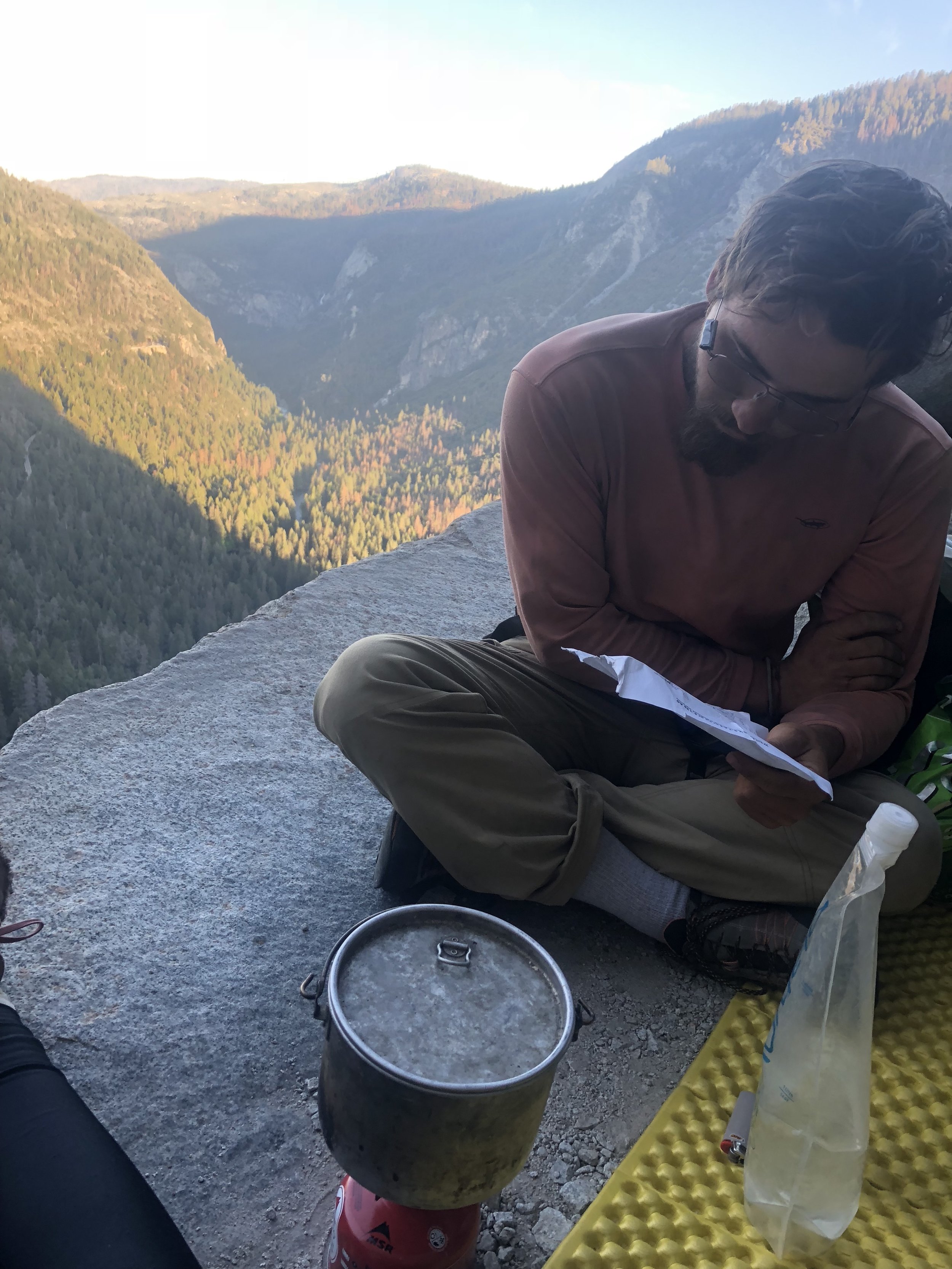

Mike looking over the topo for the West Face of the Leaning Tower

They had started climbing at 8am, and 4 hours later they got both parties off the ledge. Mike began the pitch at 12, getting used to the traversing nature of the climb and made it up to the second belay station (we linked 2 pitches into 1) around 2pm (in their defense aid climbing does takes a long time), I was standing ready with the haul bag at the base of the climb until 3:30 and didn’t start jugging until around 4pm.

We had 4 hours of daylight left and 6 more pitches to do. Even the most experienced aid climbers would have been climbing for a long time in the dark. I closed my eyes and prayed we would be in bed by midnight.

I stood with the haul bag, shifting my weight from one foot to the other, leaning back and forth, stretching my neck, my jaw, my hands, scrunching up my toes in my shoes and sighing every so often as I thought about the long night ahead.

I chose to be here.

I remind myself often. This is the price you pay sometimes for high adventure climbing.

Strangely, I had not prepared myself for boredom.

Ledge sweet ledge

“Ok Kaya ready to haul?” Mike shouts the question down to me from his position 160 feet above. I fumble with the haul bag for a minute, making sure everything is securely tied down, and then begin the process of releasing the bag or the ‘pig’ as it’s sometimes called.

“Ok Mike you’re free to haul!” I shout up to him as I slowly release the bag into space.

Turns out it’s a little nerve wracking to put all of your valuable possessions in a bag and then release them into space, 500 feet off the ground. I imagine what it might look like if the bag were to somehow break away and go plummeting to the valley floor. Everything I own; my keys, my phone, all the water and food, plus the gear our friends lent us shooting straight down into the canopy of trees below to explode on the valley floor. I wonder idly if I would ever get my stuff back.

“Ok Kaya line is fixed! You’re free to jug!” Mike shouts down at me, snapping me out of my daydream. His call marks the signal that he has tied off my end of the rope and it’s my turn to start moving up.

Let’s do this.

The very first move off the deck is a ‘lower out’. An easy but not intuitive move the follower has to do in order to avoid taking a massive swing. On a climb like this (read: super overhanging) it is very unlikely that I would hit anything, but taking a big pendulum swing can be scary and I would rather not swing out into dead space while 500 feet above the ground.

In order to do this particular lower out, I have to untie from the end of the rope. I’d done this move before: take a bite of rope, tie a not in it, clip the knot to your belay loop, untie yourself from the rope, pass the rope through the piece of tat or cord that someone else has left behind, lower out slowly and come to rest before tying back in and beginning to ascend the rope.

I know how to do this.

I’d practiced it in the gym I’d practiced it outside, I knew the motions. But as I reached down to untie my knot, for the first time in a long time, I felt the full force of exposure hit me.

I was 500 feet up, being held to this massive granite rock by nothing more than a thin emerald rope twisting off into the distance above me, and I was about to untie myself from that rope. Rationally I knew that I was also secured by both of the Jumars and the grigri and backup knot I had tied at my waist, but that didn’t stop the fear from rising up around my ears like cold water. I felt suffocated by the emptiness around and below me, it pressed on me from all sides and every muscle in my body clenched in fear.

I knew this feeling. This was panic.

Breath. Focus. Complete the move and continue up.

My hands were shaking and my mouth was dry.

I know what panic does to a person, I’d seen it before on other climbers. Panic makes you freeze, it locks your hands in place and shuts down your brain. Your judgement is impaired and you can’t see the holds or the bolts in front of your face, many people who panic come down from a climb only to look up and say “Oh man that jug right there would have saved me, I can’t believe I didn’t see it!”

Panic makes you dumb, and being dumb can kill you.

The world shrunk down to the 5 inches in front of my face as I double, triple and then quadruple checked my system.

Do not look down. Do not look down. Do not look down.

I can feel the rope stretching under my weight and fear makes me clench my stomach in anticipation.

It’s supposed to do that. It’s a rope. It’s ok.

I am in the void now. Last night I peeked my fingers over the edge to get a small taste of this empty nothingness, today I’ve jump head first into it. I’ve finished the lower out and carefully tied back into the rope. The full weight of the emptiness surrounds me as I do my best to pull my focus back to the task at hand. I cannot afford to freeze, there is no one around to save me but myself.

I do not think about falling.

I think about getting to the next piece of gear. Doing another lower out, cleaning the gear.

I do not think about falling.

I think about how this rope was a gift from a friend. She gave it to me with the advice that I check the rope before I climb on it to make sure there weren’t any flat spots.

I do not think about falling.

I think about my sister and how she is going to laugh at me and call me crazy next time I see her and I tell her I climbed a big wall.

I do not think about falling.

I think about Mike and how he’s been sitting at the hanging belay for 2 hours already and he’s probably in a lot of pain so I’d better hurry up.

And I do. Not. Think. About. Falling.

Thinking deep thoughts while staring into the void

It must have taken me an hour at least to make it to the belay station. I am pouring sweat from exhaustion, fear, or heat I can’t tell. What I can tell is that Mike is cranky from sitting at the belay for so long and anxious to get moving. We both know the sun is late in the sky and every second here is lost daylight.

“Hey, I talked to the guys ahead of us, they are going to set up their portaledge on the intermediate anchor above us, we will just pass them when we get there and keep going. It looks like we’re definitely going to be climbing the last 3 pitches in the dark.”

Mike and I are transitioning the gear as we talk. I’m organizing the rack on my harness, he’s putting me on belay, we’re handing off the haul line while we chat.

“Ok, that works for me. Man, I got really freaked out on that last pitch. The exposure got to me. I haven’t felt that afraid on a climb in years.”

He’s sympathetic but there is little to say in response, the only way out is up.

"Bail up." He tells me an we laugh at the joke.

I’m still shaking, the sun is about 45 minutes from setting, my blue patagonia base layer is clammy and damp with sweat, and it’s my turn to lead. I look up at the longest pitch on the route, almost 200 feet, and my first true C1 (aid routes are rated C1-C5) pitch. This pitch has no bolts (except for an old rusty one that sticks halfway out of the wall), so I’ll have to rely completely on my gear placements. Slotting nuts and cams into the crack, bounce testing them to make sure they hold, and stepping high up into my ladders to reach the next good placements. I will also have to ‘back clean’ a lot for this pitch, meaning I’ll have to remove gear below me once I have good gear above me so I can be sure to make it all the way to the top.

I can still feel the fear tight in my chest, I’ve never felt exposure like this before and I am rattled.

I want to be a good climbing partner, I want to prove I can make it to the top, I want to prove I am good at this.

I look up at the long, winding crack above me and then I look back at Mike. I give him a kiss before I start up. It starts as a peck for good luck, but then it hits me that I am so, so glad to have made it to him at this belay. I feel the tears well up in my eyes, a mixture of relief and fear and joy all tied into one, but I pull away and look up quickly so he can’t see how much the last pitch effected me.

My eyes are dry. Mike tells me I am on belay and wishes me good luck. I place my first piece.

It’s around 6pm when I start my first lead of the day.

Yesterday I felt strong and confident as I began my ascent, easily standing in the top rung of my ladder (also called ‘top stepping’), reaching high above me, back cleaning many pieces and generally having a good time.

Today, I am shaking. I mistrust every piece of gear I place, I question the strength of the rope, I shout down frequently to ‘watch me’ as if I might fall at any moment.

Yesterday a piece of gear unexpectedly ripped out after I had been standing on it for over 2 minutes, sending me flying through space.

Today, it’s all I can think about.

What if it happens again?

I can barely focus. I’m placing gear every 2 feet, expecting each one to pop out of the crack and send me hurtling into the air. I can feel Mike’s frustration with me at the other end of the rope, I’m barely standing straight in my ladders, and it’s taking forever.

The more gear I place the worse the rope drag becomes, the worse the rope drag becomes the harder I have to work.

I am slow, using all of my strength to stand up, getting frustrated with my ladders, and questioning all of my gear. I place a nut in a slot and bounce test it to make sure it’s going to hold.

Looks alright? Right? That’s ok. Right? I think it will hold. Right?

I transfer my weight over and —

PING!

I scream. My adrenaline skyrockets.

I haven't moved.

The nut hasn’t ripped out, but has wedged itself farther into the crack, just about an inch below my original placement. It’s the final straw.

I burst into tears. The void presses against my back.

I’m shaking with fatigue, I feel completely overwhelmed by the gear placements, by the style of climbing, and I’m approximately 700 feet in the air with a straight shot to the ground below me. The exposure has broken me.

I lean, shaking, against the wall and sob, covering my mouth with my hands instinctively so I don’t make a scene. What does it matter? There’s no one around to hear me cry anyway.

I want to be good at this. I want to trust my gear and feel secure. I want to be a good partner and a good climber. I’ve never felt so out of my element and so afraid. I look up through my tears and see 100 more feet of climbing above me, I’m barely half way.

I expect crying to make me feel better. I want it to be some kind of release that I can point to later and say, ‘All I needed was a good cry and then I was able to get my shit together and keep climbing!’

But there is no relief. I don’t feel any better than I did before and I still have a lot of climbing to do.

I wipe my eyes with the backs of my hands.

On the wall, there is no one to get you out of the situation you put yourself in except you. Mike can’t help me, the party above can’t help me, I am the only one who can make it and there is only one way out. Up.

The rest of the pitch inches along. My heart is weakly hammering against my chest, fear and fatigue waging war against my body and neither truly emerging as the victor. I’m still doubting each piece of gear and struggling to pull myself and the full weight of two ropes up the thin crack that will eventually lead me to the ledge and the belay. I pull myself up to the anchor and clip in around 8pm, the sun has just set. We have 3 more pitches to climb.

As quickly as I can, I set up the haul line and fix Mikes end of the rope to the anchor to bring him up.

Hauling is difficult for me. The bag weighs about as much as I do, making the process of pulling it up against my weight incredibly strenuous. What little strength I had left from the last pitch is slowly drained out of me as I press my legs against the wall, tighten my core and heave my body backwards in an effort to move the haul bag a few more feet into the air.

Mike makes it to the ledge just as I am able to pull the haul bag up to the belay. He helps me ‘dock’ it, or attach it to the belay and we quickly transition the rest of the gear over so he can take us to the next anchor.

We slap on our headlamps, give each other a few positive words of encouragement, and he starts up the next lead. I kiss him quickly before he leaves. There is no time for more, we have a long night ahead of us.

As he climbs away the last rays of light disappear from the sky and my world is reduced to the 2 feet in front of my face. The small white orb of light around me is all I can see. The fear and feeling of being exposed is gone. I could be standing on flat ground right now, all I can see is the anchor at my face and Mikes headlamp off in the distance.

He’s better at this than I am.

It’s true.

I watch him move easily through the massive roof above us. He pauses every so often and speaks sharply to his gear, telling it to stay, making me laugh and then he stands high up in his ladders, places his next piece without hesitation and climbs on.

The realization hits me in the dark and makes me feel very small.

As Mike is climbing my headlamp blinks three times, letting me know it’s low on battery power and about to die.

Of course.

I turn it off and am enveloped in blackness. As my eyes adjust to the dark a faint feeling of exposure comes back. You can actually see more of where you are by starlight. The smooth ghostly white granite spans out in every direction from where I stand. The stars are above me, small pinpricks of light that contrast the faint glow from the valley floor. Car headlights are driving away from the valley. I envy them for a moment, warm, safe, most likely full and about to head to a warm bed.

The last time I was warm in a comfy bed...

My mind drifts away to happier places while my body finally begins to feel the pains of the day. Although I’ve mostly recovered from the exposure on my last lead, I feel emotionally hollow, like an egg shell someone pulled the yolk out of.

My kidneys and low back are throbbing from my harness digging into them, there are red sores on my hips from the fabric rubbing back and forth on my bones, my thighs and groin are bruised and ache no matter what position I’m in. The space between my shoulder blades is screaming in protest and it doesn’t matter how I crick my neck; it hurts to exist.

Finally, it’s my turn to jug the rope.

I’m thankful for the darkness this time. I can’t see the ground below me. I can’t see the walls around me. I am moving in inky blackness on all sides, me and the thin emerald rope are the only things in existence. Every once in a while I come upon a piece of gear, fiddle with it for a moment, and then swing gently back into the void. The rock is gone. Mike is gone.

This time, the void cradles me.

I have not had enough water today. I tried to drink more at the belay but I know that considering how much I’ve been sweating, I haven’t had enough. Only about 2 liters of water all day? Definitely not enough.

I somehow forgot to unzip my puffy jacket before I started jugging, and I’ve created a sweat lodge in my jacket. More water lost. Dehydration is taking a mental toll on me.

It’s getting late as I approach the final belay station before the top. I don’t know how late it is and I don’t want to know, I just want to get to the ledge and fall asleep. We’re both exhausted from the days work, but it’s obvious that Mike has energy to spare and I don’t. My pride is wounded, but we need to be realistic. Right now what matters is speed. Drowsy climbing can be dangerous and I had to shake myself to keep my eyes open at the previous belay.

Mike starts up the more difficult pitch, C2 by the book, and I plunge myself into darkness by turning off my headlamp. There is nowhere on me that doesn’t hurt. I’ve never felt this kind of pain before. I’m not in agony, it’s not unbearable, it’s just severely uncomfortable and there is nothing to do but endure. The tendon that goes over my ankle bone is sending sharp pain up my leg, and the muscles running up the back of my neck feel stretched thin over my skull. It feels like the marrow is being pulled out of my bones.

There is nothing to do but stand in the darkness and hurt.

And wait.

And try not to fall asleep.

When it’s finally my turn I’m not sure if I am relieved or reluctant to start jugging again. My energy reserves are drained, and still I have to ascend the rope. I’m slow, dehydrated, exhausted both physically and mentally, but there are only 80 feet between me and the ledge.

As I jug the line I start to get confused at each piece of gear. My ladders are twisted up in my daisys (the cords connecting me to the Jumars), and for some reason I have a quick draw clipped to my belay loop.

How did that get there?

I have a knot tied into the rope below my grigri.

Now theres a carabiner clipped to that knot and clipped to my gear loops.

Focus. Don’t get confused. You have to focus or you might fuck something up. You're almost there, keep it together.

I can’t keep my ladders straight, they keep getting tangled and I can’t stand up in them.

Dehydration, exhaustion, fear and physical pain are making me dumb and slow. Things I’ve been doing all day long are giving me pause as I slowly remember the steps. My fingers feel thick and clumsy. My arms and legs are so tired from jugging I can barely push up my Jumars.

I’m struggling to put together the sequences of events and each time I stop I lose track of time, have I been jugging 15 minutes? 45 minutes? an hour? I reach the last section of rock, a roof you traverse under to make it to a nice big ledge. Mikes headlamp is shining brightly and I can hear him moving around setting up camp.

The last move of the day is a lower out.

Of course.

It’s difficult to explain, but in the final roof moves to the summit, Mike left me 3 pieces of gear in a horizontal roof, making it impossible for me to jug past the gear. There is lower out tat available, but it’s after a few pieces of gear farther along in the roof. To clean them I’ll need to clip in to the farthest one, remove the weight on the closest one and clean it, and then do that same move again but with the secured piece of fixed gear with tat and clean the final piece in the roof.

If it sounds confusing to you now, imagine how difficult it was for me to figure this out while jugging.

In order to move out of the roof I have to start semi leading again. I’m still secured to the rope by several points and if everything were to blow I would still be caught by the knot below my grigri.

I’m trying to transition from jugging, to leading, to jugging again all while making sure I connected to the rope by at least 3 points, oh and I have to make sure I don’t swing out into dark space. The rope is hopelessly tangled around my daisys.

I feel something burning on my knee, and as it turns out I’ve disturbed an ants nest.

Of course.

My left knee begins to burn like someone put a cigarette out on it, but pain means very little to me now.

I am 2 feet from the ledge, and I have one thought on my mind: Just make it to the ledge. I finally transition my weight over to the very last lower out move and —

My brain stops working.

I can’t remember how to do it. I’ve done at least 8 today, 5 of which were in the last 3 hours and I can’t figure out how to do a lower out.

Clip this carabiner to the piton, but theres no where to put the carabiner? When do I clip my self in to the rope?

My brain is fuzzy, my body hurts, I feel panic building up in my chest again. I’m so confused and tired I can’t think straight. The void is falsely comforting, I know I’m 1,000 feet off the deck. I feel the pressure of the empty velvet blackness pushing against me.

I figure out how to thread the rope through the tat and manage to lower myself into a final 6 foot jug to the anchors. I’m nearly hysterical at this point.

“Come on baby you’re almost there. You got this.” Mike is standing above me, just a blur of white light at the summit, I can’t see him but I can hear his voice.

I push my Jumar up, stand, push my other Jumar up, stand.

I’m almost there.

My hands crest over the edge of the ledge, relief floods my body. I push my right Jumar up the rope and —

It’s... stuck... It's stuck... It’s stuck?

Fear hits me in the face like a cold slap. “It’s stuck! I can’t move up! It’s going to cut the rope!” I squeak out at Mike. My upper body is just over the ledge, my legs dangle into the void, I freeze in space. My right arm is weakly, desperately trying to push my Jumar higher, Why won’t it go higher? What if me pushing it causes the rope to cut? I’m going to fall 1 foot from the —

Mike’s hand comes into view, I grab his arm and he pulls me the final foot over the edge. He pulls me into a hug as I collapse. “It’s ok, you’re ok. You’ve made it. You’re ok.”

Shame (and relief) floods my body and I’m thankful for the darkness; he can’t see how embarrassed I am.

Jumars would never cut the rope. Most likely my ladder was stuck on the rock somewhere and I scared myself. Somehow we’re both sitting down and I’m resting my head in Mikes lap. I’m ashamed of how I reacted and my body feels like it was thrown in a washing machine with a ton of bricks. I want to get this gear off me and go to sleep.

The worst part about reaching the summit is that there is still about 10 minutes of work you have to do before you can relax. Take off the gear, attach it to something so it doesn’t fall off the cliff, unpack your bag, grab the food and water, find a place to go pee, set up your personal anchor system so you can move around the ledge, etc. As I pace around the ledge, making myself busy and slowly regaining my ability to think clearly I reflect back on the last 5 minutes.

I freaked out. I acted like a total newb. I shouldn’t be here. I could never have done this alone. The only reason we’re here is because of Mike. Why did I think I could do this?

I apologize to him a few times for my reaction, more out of personal embarrassment than out of anything I did wrong. Freaking out wasn’t the problem, it was what the freak out represented; I wasn’t ready for this.

I needed more time to practice and I had gotten myself into a situation that was way above my skill level. It didn't feel like we were a team, it felt like Mike was taking me up a wall.

I carried these heavy thoughts with me around the ledge like unwanted baggage. I finally sit down next to Mike in one of the loveliest bivvy ledges I’ve ever seen.

The ledge slants slightly but has a natural couch like feature for us to lean our tired backs against. He’s put the flood light on so we can see without our headlamps (mines dead anyway) and set up the sleeping pads in the small alcove so we can sit comfortably while we stuff food into our faces and chug water.

A long time ago someone bolted a slab of granite upright at the ‘foot’ of the couch to make a more defined sleeping area.

“You wanna know why you freaked out so badly?” Mike says to me with a spoonful of canned Indian food in his mouth. “Why?” I say, pretending to be interested in something on my pant leg, still feeling heavily embarrassed.

“It’s 1:15 in the morning.” He smiles and snorts at the face I make when I hear him.

We’d been climbing for over 13 hours, 5 of which we’d done in the dark. “Holy shit. No wonder I’m so tired.”

There isn’t much to say after that. We’ve made it to the top but we’re only halfway done with the climb, we still need to make it to the ground tomorrow.

The rest of the night is short. We lay down in our sweat soaked clothes, our bodies incredibly sore from the days work. I check my phone right before we pass out. 1:43am. I don’t have time to feel ashamed of my performance as I lie there, I don’t have the time to reflect on how much more exhausted I am than Mike, I don’t have the energy to think about how little water I had or how little food I’d consumed that day. I don’t have the energy for anything. My head hits the makeshift pillow and I’m instantly unconscious.